Lessons (Track 1)

“Does Job fear God for nothing?” asked the accuser, the satan. (‘satan’ is simply the Hebrew word for ‘accuser’.) (The accuser could with equal justice have asked it about James and John, and we’ll get to that later.) God permitted the accuser to find out, and Job lost nearly everything. That was in the first two chapters.

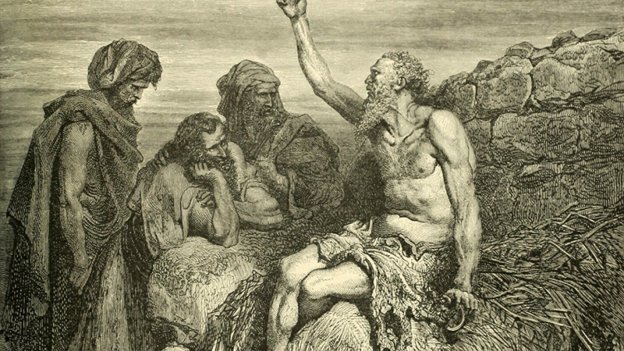

Since then, Job has been demanding action from God, and Job’s friends –I use the term advisedly—have been demanding that Job confess whatever sins have brought on his suffering. The arguments of Job’s friends don’t change much, aside from becoming increasingly vitriolic. God rules justly; if Job is suffering, he must be justly suffering, and the only puzzle is why Job is being so stubborn. What is unnerving is how often we hear these arguments today, how often we either use them or find ourselves tempted to use them. At least part of each of us, I suspect, wishes that Job’s friends were right: a completely just God insuring that each person received exactly what he or she deserved now. Some people believe in reincarnation, and one of the attractions of reincarnation is that it allows one to believe in a universe that is completely just at every moment: I am receiving precisely the mixture of weal and woe that my previous lives merit.

And even within the Old Testament, there are plenty of passages in the law that promise weal for obedience and woe for disobedience, plenty of passages in the prophets that interpret disasters as God’s punishment, plenty of passages in Proverbs that connect righteousness and prosperity, wickedness and ruin. And only a fool would deny the truth in these. But is this the whole truth? Is it the whole truth for Job? Obviously not, despite Job’s friends’ eloquent arguments.

Job’s complaints and demands for divine action do change through the course of the book. Job’s initial speech sounds like a demand that God retroactively snuff him out of existence: better never to have been born than to experience this. But as Job continues to reflect on his suffering, he recognizes that he is one of many who suffer, and his demand for God’s action correspondingly shifts: too many innocents are getting crushed.

Job is clear throughout that his problem is God: “When disaster brings sudden death, / he mocks at the calamity of the innocent. / The earth is given into the hand of the wicked; / he covers the eyes of its judges— /if it is not he, who then is it?” [9.23-24] And here, despite the rough edges, Job is speaking rightly about God. We try to protect God, buffer God from evil. Does God get joy from the suffering of the innocent? Is that his will? No. But does God continue to give breath and strength to the wicked, to keep the nerve endings working as the torturer does his work? Yes. “If it is not he, who then is it?”

We do not suffer unless God consents to our suffering. The New Testament assumes this, although notice that Paul adds “God is faithful, and he will not let you be tested beyond your strength, but with the testing he will also provide the way out so that you may be able to endure it.”

And Job pushes the limits of language, logic, and faith by appealing to God against God. “For I know that my Redeemer lives, / and that at the last he will stand upon the earth; / and after my skin has been thus destroyed, / then in my flesh I shall see God, / whom I shall see on my side, / and my eyes shall behold, / and not another.” [19:25-27]

Jesus on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The problem is not Judas, not the Jewish leaders, not Pilate: it’s God. And precisely in knowing that God’s the problem, Jesus appeals…to God. And so may we. So must we.

Well, that brings us up to the beginning of God’s response to Job in today’s lesson. Read it during the week if you can: Job 38-41. God responds to Job’s questions with God’s own questions, pointing Job to the ostrich, the war stallion, Behemoth, Leviathan, and to the challenge of mounting any useful response to the wicked.

What all that comes to we’ll wonder about next week. What I’ve focused on today is, I think, the necessary prequel to all that: Job’s insistence that God is the issue, and that only from God will come Job’s salvation, that, confronted with suffering, what we want is not explanation, but action.

This last point is, by the way, two-edged, as captured in a dialogue between two characters in a cartoon a few years back.

–Sometimes I’d like to ask God why he allows poverty, famine and injustice when he could do something about it.

–What’s stopping you?

–I’m afraid God might ask me the same question.

Our prayers for God’s intervention need to be matched by the interventions that are within our power. So, for example, as you work through your Christmas gift list, look at the Episcopal Relief and Development Christmas Catalogue. For that person who’s hard to buy gifts for or pretty much has what they need, you could give—in their name—a mosquito net, a goat, or even a cow.

Perhaps the next time through our lectionary cycle I’ll be able to give more attention to Hebrews. For the moment, simply notice that Hebrews’ portrait of Jesus looks surprisingly like Job: “In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death.” This Jesus is clearly one with whom we can be honest about our struggles.

So we turn to the Gospel—and yes, I remember that the Packers-Bears game is one of the early games. I don’t think I need to belabor our solidarity with James and John. At least from the pre-school playground all of us have been honing our skills at claiming and defending turf. It may be large, it may be small, but it’s ours and it’s for a Good Cause. And it is so easy to assume that when we are baptized, initiated into the Great Cause, the Kingdom of God, that the business of claiming and defending turf don’t change.

So Jesus has to keep reminding us: “You know that among the Gentiles those whom they recognize as their rulers lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. But it is not so among you; but whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all.”

The other James, Jesus’ brother and author of the letter, got it right: there are two kingdoms: this world, a zero-sum game in which claiming and defending turf is the only game in town, and the Kingdom of God, in which God’s generosity means that I can relax and serve.

But the text doesn’t end there, but with this final curious verse: “For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.”

We choose which kingdom we live in, and that’s true. But that’s not the whole truth. Something closer to the whole truth is that we start out enslaved to the kingdom of this world, the habits of claiming and defending turf embedded deep in us. But Jesus gave his life a ransom for many, for James and John, who on the road to Jerusalem still didn’t get it, for the Roman soldiers awaiting him in Jerusalem, for you and for me. Because Jesus has ransomed us we can choose. The gates are open; we can leave the darkness for the light.

Learning to live in the Kingdom of God is something that takes a lifetime, particularly this business of lording it over others verses serving others. And we learn it –if we learn it—in the midst of our conflicts. So think of the people –family members, colleagues, neighbors—with whom you’ve disagreed in the past and will probably disagree in the future. God can use these relationships to teach us stuff we can’t learn any other way. And here Job and Jesus do not have a monopoly on “prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears.”

Does Job serve God for nothing? Do James and John serve God for nothing, for that matter, or serve only when it helps them to claim and defend their turf? Do we? In God’s severe mercy we don’t have to answer that in the abstract, but as we find ourselves in conflict. In the words of the collect: “Preserve the works of your mercy, that your Church throughout the world may persevere with steadfast faith in the confession of your Name.”