Our second lesson picks up in the middle of one of John’s visions: a scroll in God’s hand, sealed with seven seals, and the question “Who is worthy to open the scroll and break its seals?” And whether in heaven or on earth or under the earth—the classic way of dividing up creation—no one was able, and John begins to weep bitterly.

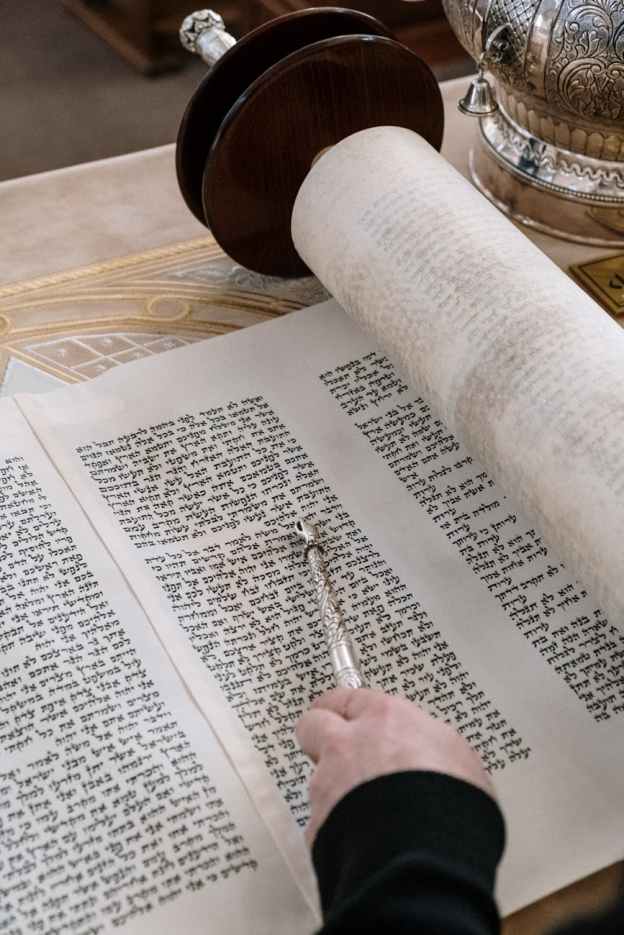

So what’s in the scroll? John doesn’t tell us. Not, I think, because he doesn’t know, but because the scroll as a symbol can do more if it shimmers a little, if it points to a number of possibilities. That scroll might remind us of the collection of scrolls that was Holy Scripture. Who can open that, offer a trustworthy and authoritative interpretation? All the divergent voices, all the dead ends: what does it come to in the end? Or, to worry about more than the Jews, the scroll might remind us of our problem of getting our head around human history. History: “one damn thing after another”? Or, closer to home, that well-sealed scroll might remind us of the challenge of understanding our own selves, our own histories. Take it in any or all of those ways, and we don’t have much difficulty joining John as he weeps.

And then one of the elders says to John, “Do not weep. See, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals.” Those two titles, ‘Lion of the tribe of Judah’, and ‘Root of David’ had been used in the centuries leading up to Jesus’ birth for the Messiah, and both promised strength, victory, conquest. With that sort of introduction, what we expect John to see is something or someone like Schwarzenegger. But what John sees is “a Lamb standing as if it had been slaughtered.”

The elder announces a Lion; what John sees is a Lamb. So what’s going on? A divine bait & switch? That’s perhaps what the crowd who cried “Crucify him!” thought. Or perhaps the most profound statement of what God’s power looks like: Jesus of Nazareth, the one who had every right to demand service, but who came to serve and to give his life—this is the slain Lamb part—a ransom for many.

And it is this Lion/Lamb who is worthy to take, open, and read that scroll in all the possible senses we noticed. Jesus, the one whose life and work is the fulfillment of that strange assortment of loose ends that we now call the Old Testament. Jesus, the one who has entered our history, and so given us the hope that it may end with something more than a bang or a whimper. As followers of the slaughtered Lamb, we live from the hope that God will bring good also out of the evils we encounter. Jesus, the one who can open the scroll that is my own life.

Jesus, the slaughtered Lamb, opening the scroll that is my life. Our other two readings give us some help imagining what this looks like, and in both cases it’s by asking questions. Jesus, of course, does more than ask questions. He gives commands (“love one another”, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations”), describes our world, tells very odd stories, weeps, laughs. But Jesus does ask questions, and that’s maybe when Jesus is most… dangerous.

Let me digress. My favorite poems are a collection of choruses T. S. Eliot wrote for a pageant play called “The Rock.” Friends in Berkeley introduced me to them; I found them in one of Berkeley’s many used bookstores in 1971. A few lines for the sheer joy of it:

We build in vain unless the Lord build with us.

Can you keep the City that the Lord keeps not with you?

A thousand policemen directing the traffic

Cannot tell you why you come or where you go.

A colony of cavies or a horde of active marmots

Build better than they that build without the Lord….

When the Stranger says: “What is the meaning of this city?

Do you huddle close together because you love each other?”

What will you answer? “We all dwell together

To make money from each other”? or “This is a community”?

And the Stranger will depart and return to the desert.

O my soul, be prepared for the coming of the Stranger,

Be prepared for him who knows how to ask questions.

Be prepared for him who knows how to ask questions.

So Saul, en route to Damascus, encounters a very bright light and a voice: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” And that question is the beginning of the transformation of his world.

And maybe only a couple of years earlier at the Sea of Galilee, the disciples after a fruitless night of fishing hear the voice of a stranger on the shore: “Children, you have no fish, have you?” They follow his instructions and end up with a net too full to bring into the boat.

Later, after breakfast:

—Simon son of John, do you love me more than these?

—Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.

—Feed my lambs.

—Simon son of John, do you love me?

—Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.

—Tend my sheep.

—Simon son of John, do you love me?

—Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.

—Feed my sheep.

Readers have long noticed that these three questions correspond to Peter’s three denials the night of Jesus’ arrest; the denials were in public, so too these affirmations. But there’s also something very intimate going on here. Peter’s responses matter to Jesus. Jesus loves Peter, and so Peter’s responses matter on a personal level. As do your responses, as do your responses, as do mine. That’s the sort of vulnerability that love brings, even and particularly to this slaughtered Lamb.

So, what questions is Jesus asking me? What questions is Jesus asking you? “Well, I don’t hear Jesus asking any questions!” Nor does someone who’s got the sound system cranked all the way up hear the call to dinner. Some noise we can’t control; some we can, and only after we’ve minimized the noise we can control are we in a position to complain “Well, I don’t hear Jesus asking any questions!”

The Lion of the tribe of Judah, the slaughtered Lamb, asking me, asking us, the questions that will open and render intelligible our lives, our world.

“Worthy is the Lamb that was slaughtered to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!”