Whether we respond to the readings with “The Word of the Lord” or “Hear what the Spirit is saying to the Church,” I take the readings to set the agenda for the preacher: what might the Spirit want us to hear today in these words of the Lord? That agenda’s in the form of a question, so most of the time the sermon’s an invitation to reflect together. So let’s dive in.

Words like ‘happy’ or ‘blessed’ appear in three of our texts. ‘Happy’ has a broad range of meanings; what are these texts talking about? Well, it looks like they’re part of a long conversation in the Mediterranean world about what counted as a life well-lived. It’s certainly about something more basic than one’s momentary emotional state. ‘Happy’ is the first word in the Book of Psalms, despite many of the psalms assuming situations that have the speakers crying “Help!” In this sense there’s considerable overlap between ‘happy’ in that psalm and Jeremiah’s ‘blessed.’

Both texts talk about two groups, their behavior and the results of that behavior. The Psalm speaks of the righteous and wicked, the behavior of the righteous captured by “Their delight is in the law of the Lord.” Jeremiah speaks of those who trust and those who don’t trust the Lord. Both use the tree image: those who delight in the law, those who trust: they’re like well-watered trees: they endure; they’re fruitful. They’re the ones who are happy (Psalm 1), blessed (Jeremiah). Trees: the image suggests a rather long timeframe. Fruit, or the effects of drought: these take time. The image is hopeful and can nourish our hope. Droughts: they’re a given; we don’t need to fear them.

So these texts are saying that in this life, this world the righteous prosper and the wicked fail? No, for starters because Jeremiah’s career is the antithesis of ‘prosper.’ They are saying that delighting in the law of the Lord, trusting the Lord are life-giving. Notice the careful language with which Psalm 1 closes (and introduces the entire book): “For the Lord knows the way of the righteous, / but the way of the wicked is doomed.”

In other words, whether all this plays out in a satisfactory way in this life, this world is left unanswered. Earlier texts often seem to assume that it does; our latest texts—like Daniel or the Wisdom of Solomon—are sure that it doesn’t. Paul’s words to the Corinthians continue this trajectory: without a resurrection in which each receive their due “we are of all people most to be pitied.”

But returning to Jeremiah and the psalm, notice that while for both of them the Lord’s torah (law, or, more broadly, teaching) is fundamental, neither narrows the focus to obeying or not obeying. Jeremiah understands that the issue is often trust, who or what we put our weight on. The psalmist speaks of delight in the Lord’s law or teaching. That’s an invitation to a life of continual discovery. Paul to the Ephesians: “test everything to see what’s pleasing to the Lord” (5:10 CEB).Cue the music from the various iterations of Star Trek, one contemporary vision of a corporate life well-lived.

Hearing Jesus’ words after Jeremiah and the psalm, we might hear them as encouragement: even if you’re poor, hungry, etc., you’re still in the life-well-lived game. And that wouldn’t be a bad way of hearing them. But there’s more.

Earlier in the Gospel Luke recorded Mary’s song. “He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, / and has lifted up the lowly. / He has filled the hungry with good things, / and the rich he has sent away empty.” Growing up with your mother singing songs like that will do things—good things—to your head. Three Sundays ago we heard Jesus reading Isaiah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor…” and here Jesus is doing just that.

“Whoa, Mary, Jesus! Pretty hard on the rich!” we might think. Well, their words reflect centuries of their people’s experience. Of course riches can be used in good ways, but usually? Sirach nails it: “Wild asses in the wilderness are the prey of lions; / likewise the poor are feeding grounds for the rich” (13:19). We shouldn’t assume that these words match our reality, nor should we assume that they don’t. (And, by the way, the next thing Jesus says—which we’ll hear next Sunday—is “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.” So however we read our situation, we’ve been told how to respond.)

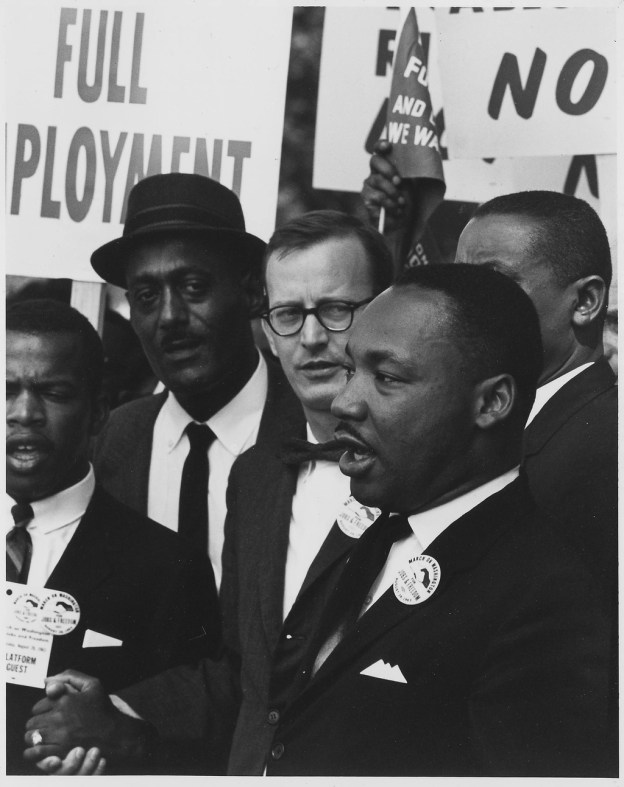

Happy those poor, hungry, weeping, hated. Not because these are positives, but because God’s reign is—as Jesus proclaims—at hand. Now, in our text we hear “for surely your reward is great in heaven.” So isn’t this another version of “pie in the sky when you die”? No, first, because the border between heaven and earth is porous, and a reward “great in heaven” is a sight better than having received all the consolation you’re going to get. Second, because of where Luke is taking this. Later in the Gospel we hear “And [Jesus] said to them, ‘Truly I tell you, there is no one who has left house or wife or brothers or parents or children, for the sake of the kingdom of God, who will not get back very much more in this age, and in the age to come eternal life’” (18:29-30; italics mine). So, describing the church in Jerusalem, Luke writes “There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need” (Acts 4:34-35). What is the Church for? It is where the truth of Jesus’ Beatitudes can be experienced.

How might we wrap this up? Already in the Old Testament we have the contours of a life well-lived: a life in which our trust in the Lord is growing, a life in which our delight in the Lord’s teaching is growing. To quibble a little with Gene Roddenberry, for all practical purposes the final frontier is not space, but the week ahead.

And with the power of the Lord Jesus’ Spirit active in our midst, this life well-lived is particularly good news for the poor, the hungry, those weeping, those excluded, reviled, and defamed on account of the Son of Man. As one of our Eucharistic Prayers puts it, “that we might live no longer for ourselves, but for him who died and rose for us, he sent the Holy Spirit, his own first gift for those who believe, to complete his work in the world, and to bring to fulfillment the sanctification of all” (BCP 374).